The UK is currently trialling a rapid Covid-19 lateral flow swab test in Liverpool.

In a previous discussion with NS Medical Devices, DnaNudge co-founder and CEO Professor Chris Toumazou explained that his own technology – a lab-on-chip RT-PCR test – is not the “moonshot” effort the government is looking for to enable mass testing, but that the lateral flow test is likely to be that candidate.

The announcement that it will be trialled in the Northern city appears to vindicate his prediction, although the test will be deployed alongside traditional RT-PCR assays as well as other newly-developed tests.

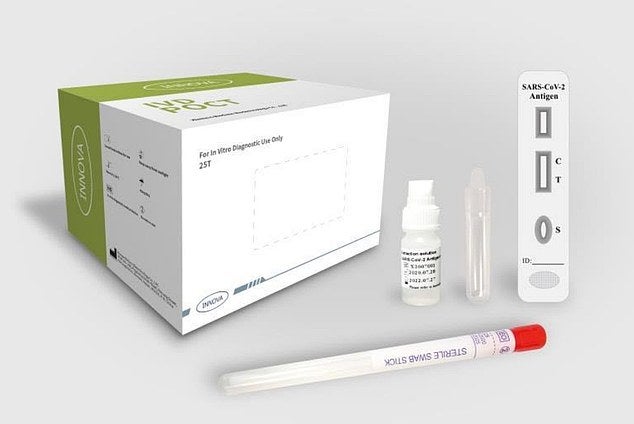

Here, we take a look at what a lateral flow test consists of and how effective it is at detecting the SARS-CoV-2 virus that can manifest as Covid-19.

What is a lateral flow test?

The lateral flow assay is a paper-based platform for the detection and quantification of analytes – the scientific name for the substance being analysed in a sample – in complex mixtures.

A variety of biological samples can be tested using a lateral flow test, including urine, saliva, sweat, serum, plasma, whole blood and other fluids.

The sample, in the case of Liverpool’s trial a swab of the nose or throat, is placed on a test device and the results are displayed within 15 to 30 minutes.

During the test, specimen extracts are applied to the test cartridges, and if there is a Covid-19 antigen in the extract it will bind to the SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal

antibody.

When passing the test line on absorbent paper, the complex is captured by the SARS-CoV-2 antibody, resulting in colouring that reveals whether or not the virus is present in the person being tested.

A control line is also present to indicate the proper liquid flow through the strip and the read-outs can be assessed by eye or using a dedicated reader.

The most common use of lateral flow testing is in diagnostics for pregnancy, which tend to test for the human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) hormone present in urine if a woman is pregnant.

How effective is the test for diagnosing Covid-19?

Low development costs and the ease of producing lateral flow tests have resulted in the expansion of their applications to multiple fields in which rapid tests are required.

The tests are widely used in hospitals, physician’s offices and clinical laboratories for the qualitative and quantitative detection of specific antigens and antibodies, as well as products of gene amplification.

As noted, the test given in Liverpool will be based on a nose or throat swab, similarly to the commonly-used RT-PCR test that’s seen as the gold standard for its accuracy.

The difference with the lateral flow test, as noted by Toumazou, is that it can be much less accurate than RT-PCR.

“The closer you are to breaking the conflict between speed and accuracy the better, and unfortunately with some of these new technologies, that trade off will be there,” he says.

The documentation attached to the lateral flow test from Innova Tried and Tested – the company supplying 20 million tests in Liverpool – claims it has an average sensitivity rating ranging between 88.75% and 99.17%.

But the lack of steps taken to amplify the viral load – a key advantage of RT-PCR – means that sensitivity could be even lower depending on factors like how long somebody has been infected by SARS-CoV-2.

This makes it especially difficult to identify those who are asymptomatic despite being infected, which is why experts have criticised the government for announcing its use as a tool for mass testing after validating its use through trials in school and hospitals across the UK.

Speaking to the British Medical Journal (BMJ), Jon Deeks, professor of biostatistics at the University of Birmingham and lead author of a recent Cochrane review of covid-19 antibody tests, said: “These are initial validation studies and should not be the basis for national decision making . . . Boris [Johnson] described these as tests of whether you are infectious, but there is no mention of infectiousness in the protocol; they are assessed as tests of infection not infectiousness.”

The government’s plan in administering the lateral flow test in Liverpool is to quickly diagnose as many people as possible as quickly as possible so they can isolate and prevent the spread of the virus.

Despite the concerns around the test’s sensitivity, which is likely to result in a lot of false negatives, it’s still the opinion of some experts that a mass testing programme administered as soon as possible will help reduce the spread.

Although he told the BMJ the details of such an operation are “thin on the ground”, Simon Clarke, associate professor of cellular microbiology at the University of Reading, said mass rapid and effective testing and isolating of infected people “really is the best way for the country to get out of this nightmare.”