The UK is facing a battle to expand its Covid-19 antibody testing capabilities — largely due to shortages of key chemical ingredients and a lack of proper manufacturing facilities. Jamie Bell speaks to a biotech industry boss and a medical devices expert about the importance of collaborations in producing enough of these critical pieces of equipment to help overcome the pandemic.

Nestled in the Hillfoot Villages of Scotland’s Central Lowlands, the town of Alva is home to fewer than 5,000 people and perhaps most famous for its Alva Games.

This event, which has taken place in a local park every summer for more than 170 years, features cycling, hill racing and, of course, tossing the caber.

As with most other public events across the world, the organisers have been forced to cancel the games due to the Covid-19 crisis — but the people of Alva may soon have some new heroes to cheer for as the town’s biotech firm Omega Diagnostics works on a coronavirus test that could help bring about a return to normality.

Like many companies in the biotech sector, Omega has answered the UK government’s plea for organisations with suitable manufacturing capabilities to come forward and help increase the country’s testing capacity.

The London-listed firm is working with fellow British diagnostic company Mologic to develop an antibody test — used to identify patients who have been infected with Covid-19, and since recovered — that may hold the key to easing the nationwide lockdown.

Omega CEO Colin King says: “I think the industry has responded very well to the call for help,” says King.

“There’s been a willingness across all companies to offer help, pool resources, and also put any previous commercial rivalries to one side and work together in the interests of finding a solution.”

“If you think about it, it probably seems like a long time if you’ve been locked inside, but it was only four or five weeks ago that we were pretty much going about our normal lives.

“And in that period of time, to be able to offer this support as an industry is actually quite exceptional — the diagnostic industry certainly has responded quickly to this crisis.”

Testing kit shortages in the UK

With the Covid-19 crisis claiming hundreds of lives each day in the UK — at least 20,000 deaths had been confirmed by 27 April — increased testing capacity has been identified by the government as a key priority.

At the beginning of April, the country’s health secretary Matt Hancock set the goal of performing 100,000 tests per day by the end of the month — no small feat for a country with a much smaller-scale diagnostics capacity compared to the likes of Germany, which boasts more than 100 labs and global heavyweights in Roche and Qiagen.

When a shipment of 3.5 million antibody tests from China was deemed too unreliable for widespread use by national testing co-ordinator Professor John Newton in early April, the situation looked particularly bleak for Britain.

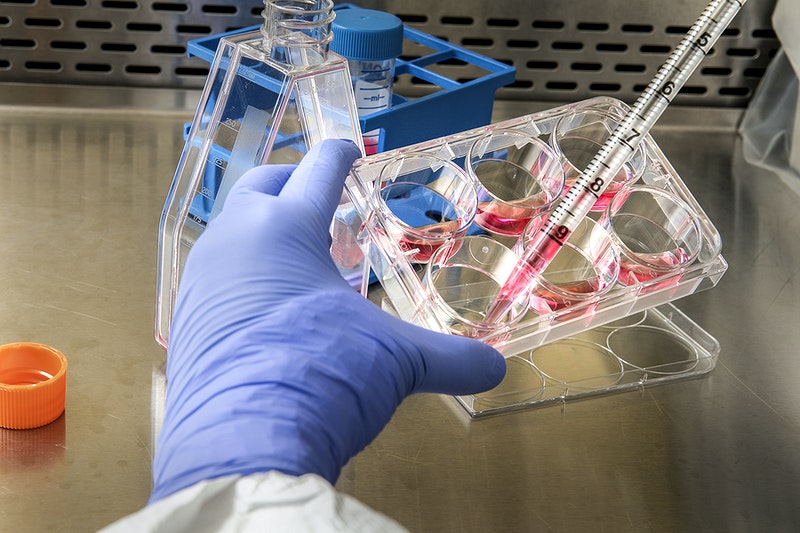

The emphasis has since shifted increasingly to the country’s biotech industry, and the need for firms such as Omega — which ordinarily produces in-vitro diagnostic (IVD) tests for patients with HIV or food allergies — to do all they can to fill this void.

In early April, Prof Newton told The Times: “There are testing manufacturers that we think could help with this. Of course, it would be great if we could have a home-produced test.”

A separate government source added: “We have some of the finest scientific minds in the world working in different areas and we want to bring people together to deliver these tests.”

How Omega Diagnostics is helping UK shortage of Covid-19 antibody testing

In mid-to-late March, Mologic approached Omega about the possibility of working together to tackle the crisis.

Before the Covid-19 outbreak, Mologic was already producing its own ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) technology, which is an established testing method for detecting proteins, such as antibodies, in a liquid sample.

Mologic’s scientists — who are providing the necessary materials and knowhow — have been given access to Omega’s manufacturing site in Cambridgeshire to make ELISA plates at a large enough scale to meet growing demands for testing kits in the UK.

Following this collaboration, Omega announced on 20 April it would be able to produce 46,000 of these novel ELISA-based antibody tests per day.

Mologic CEO Mark Davis described this as an “exciting development” in the global pandemic response.

“With the capability to process tens of thousands of test results every day, these kits will relieve immediate testing pressures in the UK and Africa,” he added.

The final hurdle before this mass production can begin is EU medical device regulation — although Omega CEO King is hoping the new test will gain a CE marking for use in Europe within days.

Omega and Mologic are both heavily involved in several lower-to-middle income countries, particularly in Africa, where King acknowledges there is also a significant demand for these testing kits.

But he says that ultimately, if the UK did ask for the entirety of this 46,000-strong daily supply, Omega would oblige.

“It really comes down to the UK government and how much of the production it needs,” King adds.

“It is a lab-based test, so it may not want all 46,000 tests because of the workloads it creates in these laboratories — it requires a skilled technician to be able to run the tests, and it will take a few hours to process and get results.

“So, on the logistical side of things, there are justifiable reasons why the government may not want to take on all our production.”

There’s also the question of accuracy to confront. It was a failure to satisfy a standard that says tests must give the accurate answers at least 95% of the time that led to the 3.5 million Chinese kits being rejected, with Hancock saying “no test is better than a bad test”.

King claims the Omega-Mologic antibody test is as close to perfection as humanly possible, with 98% accuracy — citing a successful collaboration as the reason, given the raw materials used to make them must be of high enough quality to return such results.

“It’s like baking a cake,” he explains. “If you don’t start with the proper ingredients, then the chances are it’s not going to turn out as well as if you use better quality ingredients.

“That seems to be what Mologic has provided — those critical materials they’ve developed are of a very high quality.”

While many biotech companies such as Omega are already well-equipped to cope with the growing demand for testing kits, that doesn’t mean answering the proverbial call to arms at the beginning of April has been without its challenges.

“We have had to reconfigure both of our sites — mainly around social distancing,” says King.

“We have the capacity to manufacture these products but we’ve had to reconfigure some of our working areas.

“We’re about to bring more people on site next week, so we’ve had to relocate people in different areas of the factory to make sure that they’re two metres apart.

“But we’ve been able to do that because many people are working from home rather than being present in the facility — that has allowed us to use some other areas that may not have been available previously, and convert them into manufacturing areas.”

Antibody tests – the key to ending UK lockdown?

According to the most recent estimated figures from online science publication Our World in Data, the UK experienced its most prolific day of testing so far on 26 April, with a little more than 29,000 being performed.

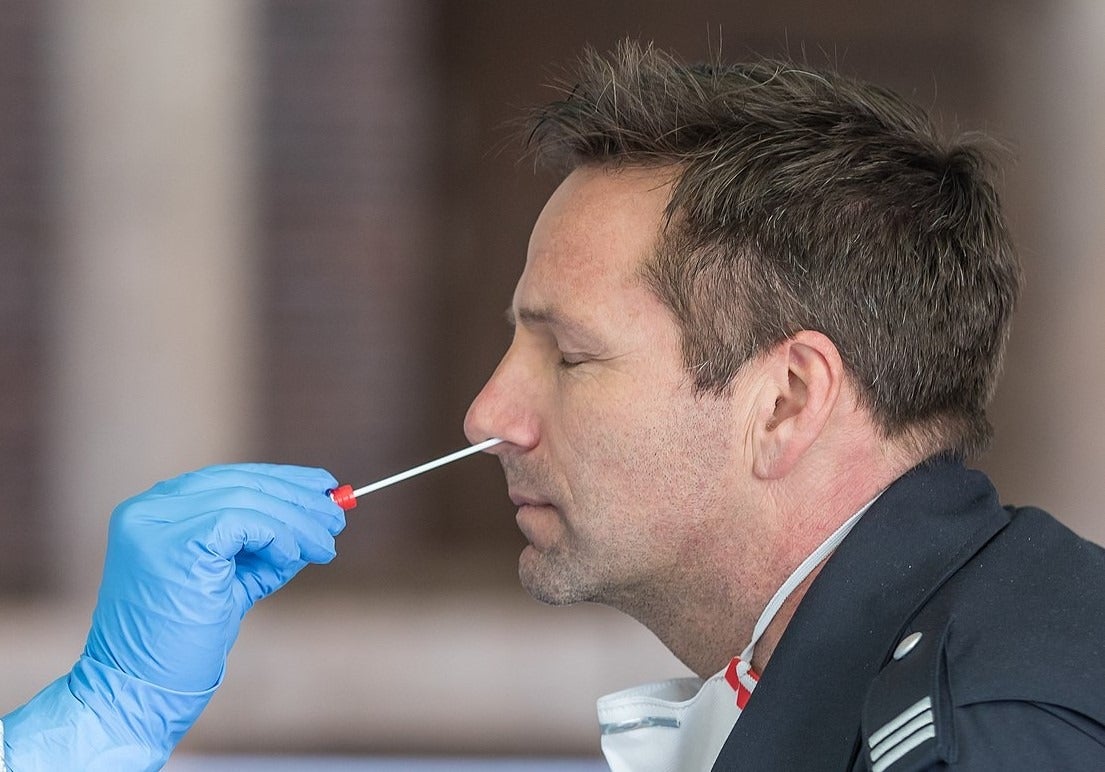

Yet these figures, and Hancock’s daily goal of 100,000 tests, are thought to mainly consist of the antigen version of Covid-19 tests.

Through much of the pandemic to date, the UK has prioritised production of antigen tests, which involve taking a sample from a patient’s nose or mouth, using a swab, and testing it for SARS-CoV-2 — the virus that causes Covid-19.

These are primarily being used to diagnose patients who are currently infected with coronavirus in hospitals across the country.

But as time passes, and with no real end in sight for the national lockdown, increasing emphasis is being put on ramping up production of the other main type of Covid-19 testing kit — the antibody test.

In a joint statement on 1 April, the Association of British HealthTech Industries (ABHI), BioIndustry Association (BIA), and the British In Vitro Diagnostic Association (BIVDA), said testing the general population for exposure to SARS-CoV-2, using these antibody tests, will be important.

“In the coming weeks, the government will need to prepare for the next phase of the Covid-19 response,” they added.

“Attention, therefore, must turn to antibody testing to complement virus testing. It is paramount that effort is directed to support innovators who are working in this field, to enable a secure supply chain of high quality, validated products.”

While antigen tests are used to diagnose currently infected patients, antibody tests detect the presence of the body’s immune response to the virus, and can, therefore, be used to identify previously-infected people who have since recovered.

Although definitive scientific evidence of immunity from reinfection remains absent, it’s generally believed those who test positive wouldn’t be able to spread the virus further, at least in the short term — enabling them to be “released” back into society.

The impact this could have on the population at large is considered to be two-fold – enabling scientists to map out the true spread of the virus since the first case was reported in 29 January and providing a desperately needed boost to the UK economy.

Small and large businesses alike have been forced to furlough millions of employees, oil prices have turned negative for the first time in history, and a long list of British companies have entered administration due to Covid-19 — leaving thousands more unemployed.

So not only will large-scale antibody testing allow doctors, nurses and other NHS employees to get back to treating patients, but a return to normality may not be far behind as people in other jobs gradually get back to work.

Will supply problems hamper widespread antibody testing?

Around the same time Hancock set the target of 100,000 daily tests by the end of April, cabinet office minister Michael Gove conceded that a shortage of raw materials was obstructing the UK’s attempts to expand antigen testing capabilities.

This is because antigen tests require several chemical reagents that are not usually in such high demand — as well as physical components such as the swab used to take a sample, and the container it is then stored in.

Dara Lo, a medical device expert at analytics firm GlobalData, believes many of these problems could also impact attempts to ramp up production of antibody tests further down the line.

But she adds this is only likely to materialise once there is a greater demand for them.

“As more countries became aware of the growing pandemic, and as more biotech companies began entering this space, the demand grew and grew — and they’ve all been drawing from the same supply,” says Lo.

“This excess in demand far outstripping available supplies is where we start to see a bottleneck in the supply chain.

“We don’t see that yet for the antibody tests because they are not relying on the same supplies, but if we’re modelling this based on what we see with those PCR-based tests [a method of antigen testing], you can imagine how that might become a bottleneck too.”

Despite this, Lo believes “only time will tell”, adding the urgency around antibody tests may never be as great as the urgency around antigen testing.

“The timing is not as critical,” she says. “The demand for PCR supplies has just been through the roof because that is one of the primary tools to control the spread of Covid-19.

“But, with antibody testing, it’s more of a tool that we can use to see when we may be able to end social distancing and the lockdown.

“I would just be speculating, but I wouldn’t expect the antibody testing to have as much urgency as we saw around the PCR-based ones.”

If that is the case, there may end up being fewer supply problems, and a less severe shortage of important chemicals used in the antibody tests, according to Lo.

At-home testing may be on the horizon

The venture with Mologic is only one half of what Omega is doing to contribute to the UK’s antibody testing capacity.

In what King describes as a “non-Covid world”, these ELISA-based tests are more than suitable for testing patients for certain antibodies. They are cost-effective, and can be analysed in bulk inside a laboratory.

However, with testing being more urgent than ever during this crisis, attention is also turning towards another method of antibody testing, referred to as a lateral flow test.

These kits are similar to a standard pregnancy test, in appearance at least, as they consist of little more than a test stick.

Like the ELISA-based test, they work by analysing a blood sample for antibodies — although they can be used at home by patients, and they don’t need to be sent off to a lab for results because the test stick itself provides a positive or negative reading within minutes.

As part of a biotech consortium with three other UK firms — London-based diagnostic company Abingdon Health, BBI Healthcare and CIGA Healthcare — Omega is working to develop, and ultimately mass produce one of these lateral flow testing kits.

The group is being referred to as the UK Rapid Test Consortium (UK-RTC).

Chris Yates, CEO of the UK-RTC’s leading partner Abingdon, said on 9 April: “We have an excellent team of scientists with many years’ experience in both rapid test development and large-scale manufacture.

“Partnering with others in the consortium means we will be able to scale the product to the desired volume quickly following successful development and we look forward to working with our partners to achieve this.

“The beauty of the consortium is that all four parties have the development skills and the ability to manufacture at scale,” says King.

“We’re very clear on how much each partner can make today, but also how we could expand that further as well — and that’s what we’re working on now.”

“We’ve also noticed that each partner is based in one of the four UK countries, so, conceptually, we [Omega] would supply Scotland, Abingdon — the group’s leading partner — would supply England, BBI would supply Wales and CIGA would supply Northern Ireland.

“But clearly, England is by far the biggest, so the likelihood is that any excess capacity from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland would then feed into ensuring the greater English demand is met as well. Conceptually, that’s how we envisage it.”

Using testing methods and chemical reagents provided by the University of Oxford, King believes Omega alone already has the capacity to produce 100,000 of these lateral flow tests per week — and that’s before any potential scaling up of production that may yet take place.

Despite these promising numbers, there is no specific timeframe for when these testing kits may be available for public use — while King says the ELISA-based tests will most likely come out “in a matter of weeks”, the at-home kits will not be available in the same period.

“But we’re obviously working incredibly hard to deliver that as quickly as we can, and we understand the importance of getting that test to market as soon as possible,” adds King.

The importance of biotech collaborations

Both of the projects Omega is currently involved in demonstrate the importance of firms combining their expertise, materials and facilities to meet demands for Covid-19 testing.

GlobalData analyst Lo believes these companies are as well-placed as anyone to help the UK follow the examples of countries such as South Korea, Germany and China that have been lauded for their approach to testing in recent weeks.

“They already have the appropriate resources and infrastructure in place, and have previously developed those products and those relationships in terms of manufacturing, developing, and researching these tests,” she adds.

“When it comes to validation, and making sure these kits are up to safety standards, they’re using structures that are already in place because they have launched similar products before. On the regulatory side of things, that’s very important.

“We have the pandemic on one hand, but we also still need to make sure that things are up to standards before they are released to the general public.

“Companies in the biotech industry are able to do that very quickly and very smoothly while still meeting those standards.”

There are plenty of other instances in which biotech companies have collaborated with the wider healthcare industry in recent weeks.

One of the most notable examples — alongside Omega teaming up with Mologic — came earlier this month when Anglo-French diagnostics firm Novacyt joined forces with UK pharma giants GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and AstraZeneca.

Meanwhile, GSK is also collaborating with US biotech company Vir in an effort to discover a successful vaccine candidate for Covid-19.

King is pleased to see more industry link-ups like his own popping up on a regular basis.

“These collaborations are critical and during the crisis, there’s an immediacy to the need to work together,” he adds.

“In terms of our relationship with Mologic, we have worked with it in the past, but I’ve been really impressed with the way both teams have worked together to execute something that typically would take months, and has been carried out in days and weeks.

“There’s been a willingness from these people to work longer hours, to work over weekends to just get through this and bring forward a product that will hopefully help to get us back to normal – whatever normal is.”