The pressure on healthcare services caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has forced those in charge of them to think differently about how patient care is delivered. Telehealth was one of the first adaptations made, and now remote appointments have been validated as a useful tool, organisations are beginning to accept the role that digital-health monitoring is likely to have in future healthcare practice. Peter Littlejohns talks to OMRON Healthcare’s Paul Stevens about how the company aims to battle hypertension in patients using remote patient monitoring technology.

Hypertension is known as the silent killer due to its lack of symptoms, yet it raises the risk of heart disease and stroke – the two leading causes of mortality worldwide – as well as a number of other serious or potentially life-threatening conditions.

There has long been a medical imperative to control high blood pressure, the colloquial term for hypertension, but even now in our digital age management plans tend to extend to a single blood pressure measurement taken at the doctor’s office during infrequent check ups.

According to Paul Stevens, OMRON Healthcare Europe connected services and solutions director, this approach doesn’t always paint the most accurate picture of how a patient is managing their condition.

“Usual care is that a patient diagnosed with high blood pressure will have a series of appointments in which a doctor will measure their blood pressure and change the treatment plan depending on that reading,” he says.

“But there’s a lot of evidence one-off readings like this are not particularly accurate for a number of reasons.

“Maybe somebody has just run for the bus to get to their appointment, or had a coffee just beforehand.”

It’s because of this margin for error that the initial diagnosis of hypertension requires a patient to take a series of home measurements, or wear a continuous blood-pressure monitor for a day.

But once a patient is diagnosed, Stevens says it can take up to six appointments to get them on a control medication, and even then the lack of accuracy could mean their dosage isn’t right for the initial prescription or for subsequent changes.

Once their blood pressure is under control, patients will usually have annual checkups that involve another single-point-in-time measurement, and if that’s okay it’ll be another 12 months before the next.

“If their blood pressure changes in that time, it’s only picked up at that appointment,”

“There’s a lot of opportunity to support people in having closer control, as well as giving the patient and clinician more confidence in the data used to make decisions.”

Clearly, the NHS is aware of these benefits, as OMRON’s solution to the problem is being rolled out across more than 150 UK healthcare practices within the service right now – but it wasn’t a straightforward path to begin this adoption.

The science and value behind remote patient monitoring for hypertension

OMRON had been working on Hypertension Plus for a number of years prior to the UK rollout.

According to Stevens, the project that led to the technology was inspired by the work of Oxford Professor of Primary Care and general practitioner Richard McManus, an academic internationally recognised for studying the management of hypertension.

In a paper composed after one of these studies, which included 1,182 participants, McManus and his team wrote: “Self-monitoring, with or without telemonitoring, when used by general practitioners to titrate antihypertensive medication in individuals with poorly controlled blood pressure, leads to significantly lower blood pressure than titration guided by clinic readings.”

Stevens explains: “We saw his work, and actually he used OMRON devices in a number of his studies.

“He got to the stage where he’d proven in large studies that the principles worked, and he wanted to see his contribution rolled out in a way that impacts real people’s lives.

“We reached out to Richard and said we think this is somewhere we can help in terms of bringing the work done in a clinical studies setting into the real world.”

Work on Hypertension Plus began in 2018, the same year that study was published.

But although the benefits of remote patient monitoring for hypertension have been clear for a while, it took a pandemic to create the circumstances that forced the hands of healthcare providers into their pockets.

How Covid-19 changed the equation

Digitising aspects of health management always carries an initial cost, and despite the potential savings made through freeing up doctors’ time, service providers can be reluctant to adopt new ways of working.

But Stevens says cost wasn’t a major barrier for the NHS, which gets the majority of its funding from the UK government.

“The cost wasn’t such an issue, because Hypertension Plus is, in principle, a net saving for the healthcare system, even at GP practice level, because we’re able to optimise how the staff are spending their time,” he says.

“Some of the main questions were ‘will patients want this? Will they want to do things remotely or will they still want to come and see us?'”

It was this uncertainty around patient uptake and usage that kept the hands of decision makers hovering above their pockets – but then a pandemic happened and telemedicine became a reality for many.

“The feedback from patients was that they liked having those different ways to contact GP practices,” explains Stevens.

“There’s still a time and a place for face-to-face consultations, and that won’t go away, but there are many things that can be done remotely, and patients are more embracing of that than the medical community to some extent.”

The capacity to conduct virtual medical appointments over video call has been there for more than a decade.

But although the use of telemedicine has increased in recent years, the ratio of in-person to remote consultations still sways heavily in favour of the face-to-face approach.

One reason for this is that in Europe, North America and many other regions, regulatory rules around data privacy haven’t allowed telemedicine to proliferate.

But as Covid-19 made virtual appointments a necessity to avoid the spread of infection, these rules have been relaxed to a large degree, and in accordance with positive patient feedback, has created what Stevens refers to as a “sea change” in appetite for remote healthcare technologies.

The NHS itself established a new wing (NHS At Home) designed to push the use of connected care technologies in response to the disruption caused by the pandemic, and it’s this push that led to the rollout of Hypertension Plus.

“The conversations we were having before Covid-19 were around encouraging people based on the benefits of digitisation and remote patient monitoring,” he adds.

“Now, there’s an acceptance that remote patient monitoring is the way forward, and the conversations are around what is the right tool for each practice.”

What makes Hypertension Plus the right remote patient monitoring tool?

It’s promising for OMRON that Hypertension Plus is being adopted in the UK – but with 6,813 GP practices in the country, it’s also fair to assume that a commitment to use the technology in 150 of these is more akin to a toe in the water than diving right in.

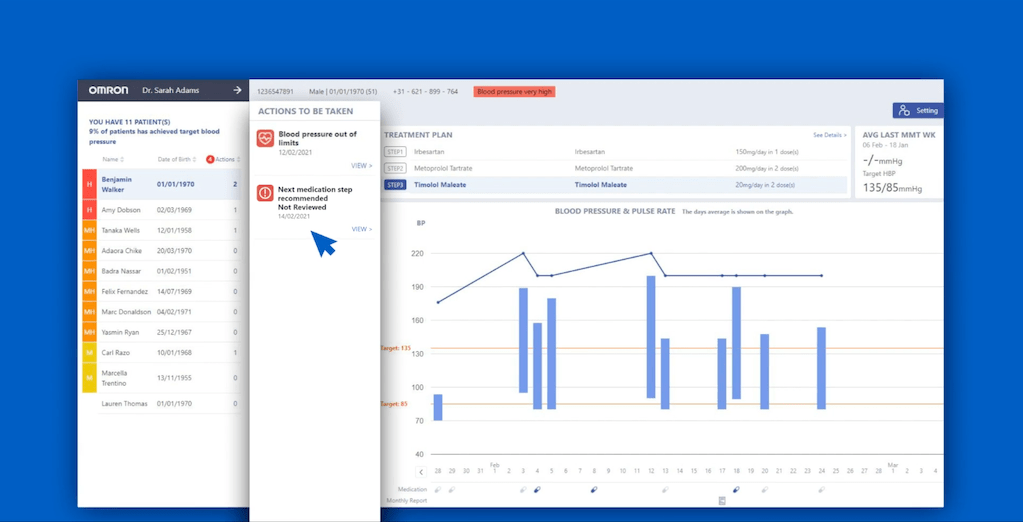

The product set that Stevens and his team are relying on to extend this rollout in the future are a desktop software on the clinician side, and a smartphone app on the patient side, both tied together by a hypertension management plan setup under National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines.

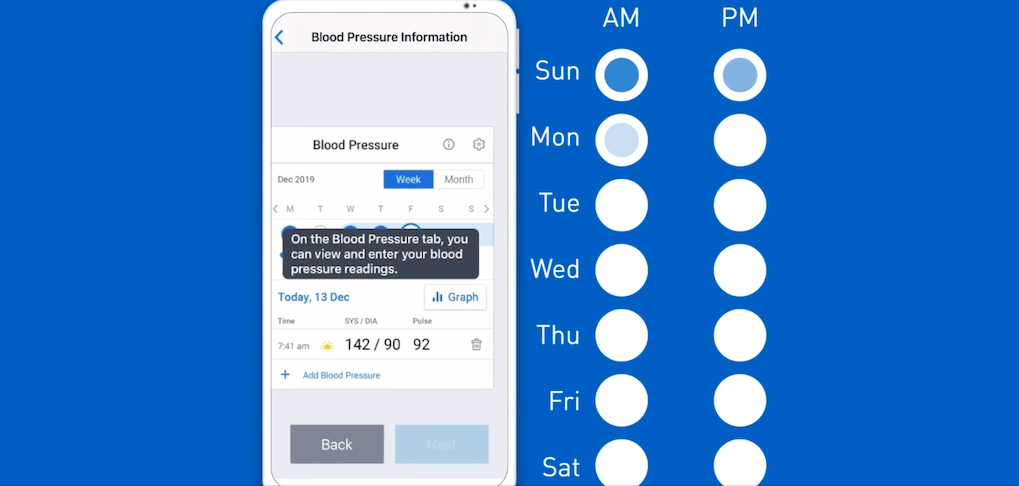

Once this plan is established and a drug titration schedule is set, the app prompts patients to record and input their blood pressure to create several readings that can be averaged to avoid the inaccuracy of a single measurement approach.

All this time, the data collected on each patient updates the risk profile on a GP’s desktop programme, which will alert them if an increase in risk requires an adjustment to their antihypertensive medication.

This change is again based on NICE guidelines, and doctors can review the suggestion and modify or approve it when ready.

As with any app-based management tool, Stevens admits that there is an element of digital exclusion risk in adopting Hypertension Plus – although he believes this is somewhat offset by recent smartphone use statistics.

“There’s no escaping that there is a difference in digital inclusion between age groups, but the aim of Hypertension Plus is to make the patient experience as intuitive and simple as possible.

“The national statistics on smartphone ownership and digital inclusion show year-on-year, even in the older age groups, it’s becoming more common to own smart tools and to know how to use them.

“While we need to be conscious of those that can’t, and put in place services for them, we also need to realise that over time, higher and higher percentages of the population will want to access healthcare in that way.”

The most recent Ofcom survey on the topic found that, out of 3,600 respondents, 5% of those in the 35-54 age group did not own a smartphone, compared with 30% in the 55+ age group, leaving a majority of 70% that did.

Beyond the UK and beyond hypertension

Hypertension is a problem around the world, and OMRON Healthcare, a Japanese firm with divisions in several regions, wants to spread the benefits of Hypertension Plus further than the UK.

But Stevens says the regulatory and structural makeup of healthcare systems in other countries necessitates the need for different approaches.

Systems like the NHS, in which healthcare is provided free at the point of service and hypertension is primarily managed between a patient and their GP, are what he calls the “low hanging fruit” for OMRON right now.

“We’re particularly looking at France, Spain and Germany as key next steps,” he says.

“France and Spain are very similar setups in the way that patients are managed through primary care.”

Germany, he adds, is a different use case because of the way the country splits management of long-term conditions between primary care physicians and specialists.

OMRON did expect the Digital Health Applications Ordinance (DiGAV) regulatory change made to push more remote healthcare management in the country to create fertile ground for Hypertension Plus to grow – but the change emphasised individual health management over a joint approach between patient and physician.

This, however, Stevens expects to change in the near future as remote patient monitoring tools like Hypertension Plus prove their worth elsewhere.

On the other hand, insurance-based health systems like that of the US, make it harder to implement the technology.

“We have a system called VitalSight in the US, which doesn’t have the same algorithmic automation as Hypertension Plus,” Stevens says.

This US product allows patients to track their blood pressure and weight, and the data is stored within their electronic health record, where physicians can request it, but will only be alerted to risky results if they set a parameter for the feature

But Stevens adds that there is a mechanism within the Medicare system to reimburse insurers for offering healthcare management tools within their networks, and this is laying the groundwork for more automated approaches.

Looking beyond hypertension, he believes the management of long-term health conditions in general will be an area to experience significant innovation now that Covid-19 has increased the appetite for them by proving that patients want to use them.

“People with long-term conditions are around 30% of the UK population, but they take up about 70% of healthcare resources and 50% of GP appointments,” Stevens concludes.

“While we’re going to market now with Hypertension Plus, our intention is to apply the same management logic to other long-term conditions.”