Heart disease is the leading cause of death worldwide, and mortality risk often depends largely on when a condition is diagnosed and treated. Depending on patient risk factors, diagnosis and treatment planning can require invasive procedures. HeartFlow chief medical officer Campbell Rogers explains to Peter Littlejohns how 3D heart scans are giving doctors a better tool for screening which patients require invasive surgery.

Coronary artery disease is the most common form of heart disease, but the associated symptoms can be indicative of a range of maladies.

Despite this, physicians can be quick to order an invasive test if traditional screening methods confirm their worst fears.

At least this is according to former physician Campbell Rogers, who swapped a career in the cardiac catheterisation lab to join HeartFlow, a company seeking to improve the care pathway with new technology that creates a 3D model of the heart.

“When I was in practice, I did invasive procedures, and the pathway that leads to them traditionally leads through non-invasive tests, such as a stress tests for example,” he says.

“Usually this is done because they’re having symptoms like chest pain or breathlessness, or anything that would make a physician think they might have blockages in the arteries.

“The problem is that those tests are notoriously inaccurate.

“People come in because their physician is worried that non-invasive tests suggest they have blockages in the coronaries, and lo and behold, we do an invasive procedure and there are no blockages causing the problem.”

The account given by Rogers appears to be reflected in much of the literature surrounding diagnostic testing for coronary artery disease – a phrase often used interchangeably with heart disease owing to it being the most common malady of the heart.

In one 2017 study carried out at a district general hospital in the UK, it was found that out of 707 patients who underwent coronary angiography – the name of the diagnostic test that requires cardiac catheterisation – 275 had normal arteries or atherosclerosis (plaque build up) so mild it required no treatment.

The risks and cost of cardiac catheterisation

In all of the cases in which a coronary angiogram finds no evidence of blocked arteries, patients run the low but ever-present risk of stroke, heart attack, and according to Rogers, even death.

Rogers joined HeartFlow a few years after it was founded in 2007 with a dual purpose to improve the cost and decrease some of the risk inherent within heart disease diagnostics.

“I see it through a clinical lens, but people that pay for healthcare see it through a financial lens as well, and that journey, including invasive procedures, is really expensive.

“They’re done in operating room facilities, they require nurses, technicians, specialist physicians for instance, and the bill for those is significant.

“What appealed to me about Heartflow, and what has proven to be the case, is that there is a much better way to do this that doesn’t require that invasive test, saves the system money and avoids those risks to patients.”

Coronary CTA

Despite the inaccuracy of many non-invasive tests, one tool that remains a necessity even with HeartFlow in play is the coronary CT angiogram (CTA).

During this procedure, a fluorescent dye is injected into the patient before they undergo a CT scan, and Rogers says this particular technique has evolved significantly over the years.

“If you go back nine or ten years, coronary CTA existed, but it has evolved tremendously over the last decade for two reasons.

“One is that the equipment made to get the scans has become much better. The pictures they get are much higher fidelity.

“The second is they have become much more parsimonious about how they use radiation.

“These are X-ray tests but the radiation exposure to the patient has become much lower, meaning doctors are more likely to prescribe them.”

Rogers further explains that data has been gathered over the last ten years, much of it in accordance with HeartFlow, showing that a CTA is a better investigative tool than a stress test.

One of the most pivotal studies surrounding the use of CTA in diagnosing heart disease is the SCOT-HEART trial.

The study involved 4,146 patients attending the rapid-access chest pain clinic for the evaluation of suspected cardiac chest pain.

“This study showed really quite conclusively that if you take patients and manage them based on a stress test and add a CT scan to the pathway, their outcomes are much better, and their risks of dying or having a heart attack are reduced by more than 40%,” Rogers added.

What the study didn’t do, however, was reduce the number of patients being referred for an invasive coronary angiography – the number actually increased slightly – which is why HeartFlow had to take the evolution of the test one step further.

How does HeartFlow help patients avoid invasive tests with 3D heart scans?

Even with the conclusive evidence provided by the SCOT-HEART trial, the status quo was fairly entrenched within the medical community.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK updated its guidance in 2017 to dictate that a coronary CTA should be the first test in the care pathway for suspected heart disease, which Campbell says put it ahead of the curve, with the rest of the world catching up over time.

But there was still a need to reduce the number of patients going in for a coronary angiogram, which is where HeartFlow’s technology comes into play.

“In patients where the CT scan is not normal, where it shows some disease, HeartFlow provides important additional information that helps keep patients from going through invasive procedures unless they really need to.

“The two tools together have become a very compelling value proposition.”

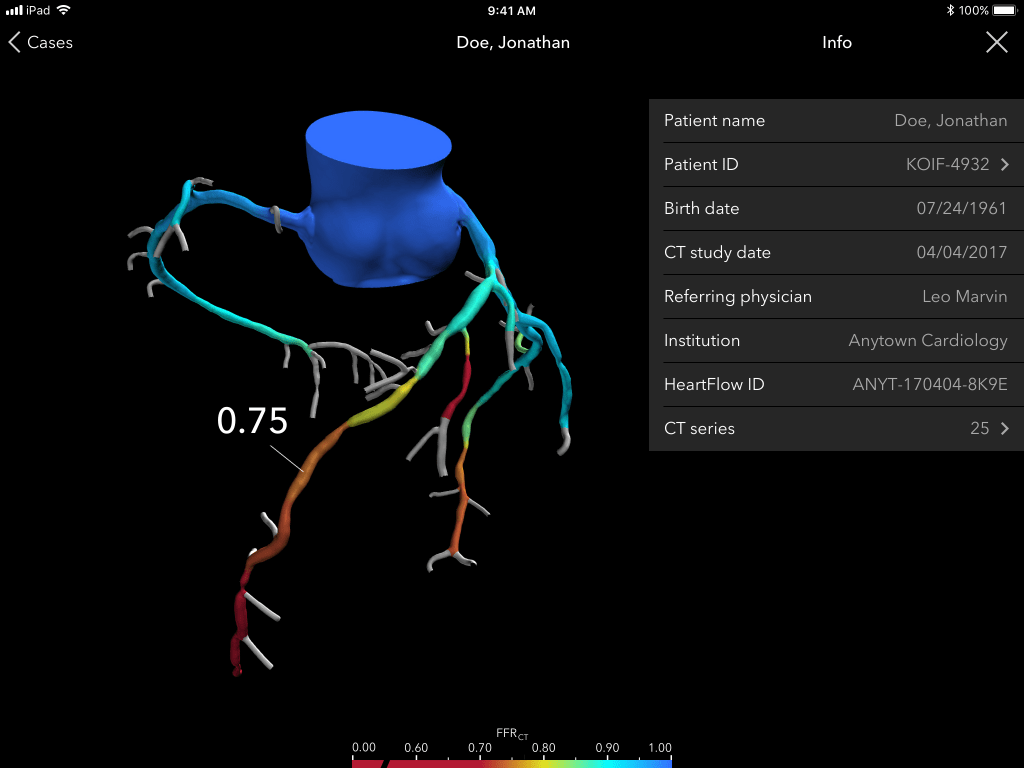

While a CTA can show areas of calcification or other blockages that have narrowed the arteries, it cannot give doctors an understanding of how that narrowing has impaired blood flow to the heart.

“It’s not a direct relationship,” explains Rogers.

“Two people may have a 50% narrowing in their main artery down the front of the heart, but one person may have a really significant limitation in blood flow that needs fixing with a stent, while the other may have much less flow reduction and can be managed with tablets alone.”

It’s this information on flow reduction that HeartFlow provides by taking a coronary CTA and turning it into a 3D map of the heart and arteries, showing areas of narrowing in more detail and providing a clinically-recognised metric called fractional flow reserve to reveal how that narrowing is impacting blood flow.

This same metric would be obtained via invasive coronary angiography, but HeartFlow’s 3D heart scans and computational fluid dynamics have been shown to match the findings of the surgical test.

The nuts and bolts of the operation involve the use of machine learning algorithms and human analysts on hand in one of HeartFlow’s two centres in Texas or California, and Rogers says the company has a 95% success rate in transforming CTAs into 3D scans, meaning in 5% of cases the quality of the heart CT scan is too low.

The process itself tends to be required for between 30% and 40% of patients in an average population without an elevated risk of heart disease, he adds, and it can take between two hours and five hours, with the lower timeframe met for high-risk patients if hospitals flag their application with HeartFlow.

The future of HeartFlow

The NHS has been using HeartFlow to speed up heart disease diagnosis since May 2021, and Rogers says much of the traction in the US has come from hospitals seeing the success of the company’s care pathway in the UK.

Across the pond, 37 of the top 50 cardiovascular hospitals have adopted HeartFlow, according to the company’s website.

Another major market for the company has been Japan, with its ageing population and an aversion to invasive procedures creating a perfect opportunity for doctors to use the analysis technology, explains Rogers.

But there is still commercial opportunity within Europe, he adds, especially since NICE released its latest review of the technology in 2021 and noted a cost-per-patient saving of £391 on average – and that’s before the cost of a coronary angiography was considered.

Much of Europe looks to NICE for guidance on new technologies like HeartFlow, but Rogers says the Netherlands, which tends to conduct its own reviews, has agreed to fund its own study into the use of the HeartFlow care pathway through its own advisory body, Zorginstituut Nederland.

On top of these efforts to expand the reach of its 3D scans, Rogers says the company is looking into ways it can adapt the product to reveal more information about the heart and other vasculature.

“CT scans show blockages, but there’s a lot of information about what those blockages are composed of and how that can define patient risk.

“There are ways in which we at HeartFlow can take advantage of all of the scans we have and our image analysis competencies to provide back to clinicians information about the composition of plaque in the arteries.

“That’s an area we’re very actively pursuing, entering into clinical studies about and seeking regulatory approvals for.”

In the longer term, HeartFlow plans to branch out into other areas of the vascular system that can also be imaged reliably via CT scan, like the legs for instance, but for now the focus remains on the organ that inspired their product in the first place.