While the world’s biggest pharma companies have entered into a race against time – and each other – to develop a Covid-19 vaccine, several smaller teams across the globe are working on an adhesive skin patch for immunising people against the virus.

Investigations into a coronavirus vaccine patch may be in the early stages but, if successful, they could lead to a more convenient, pain-free alternative to administering vaccinations via an injection.

We take a closer look at how these novel technologies work, which companies and research teams are attempting to bring them to the world, and when a Covid-19 vaccine patch is likely to be available.

How does a vaccine patch work?

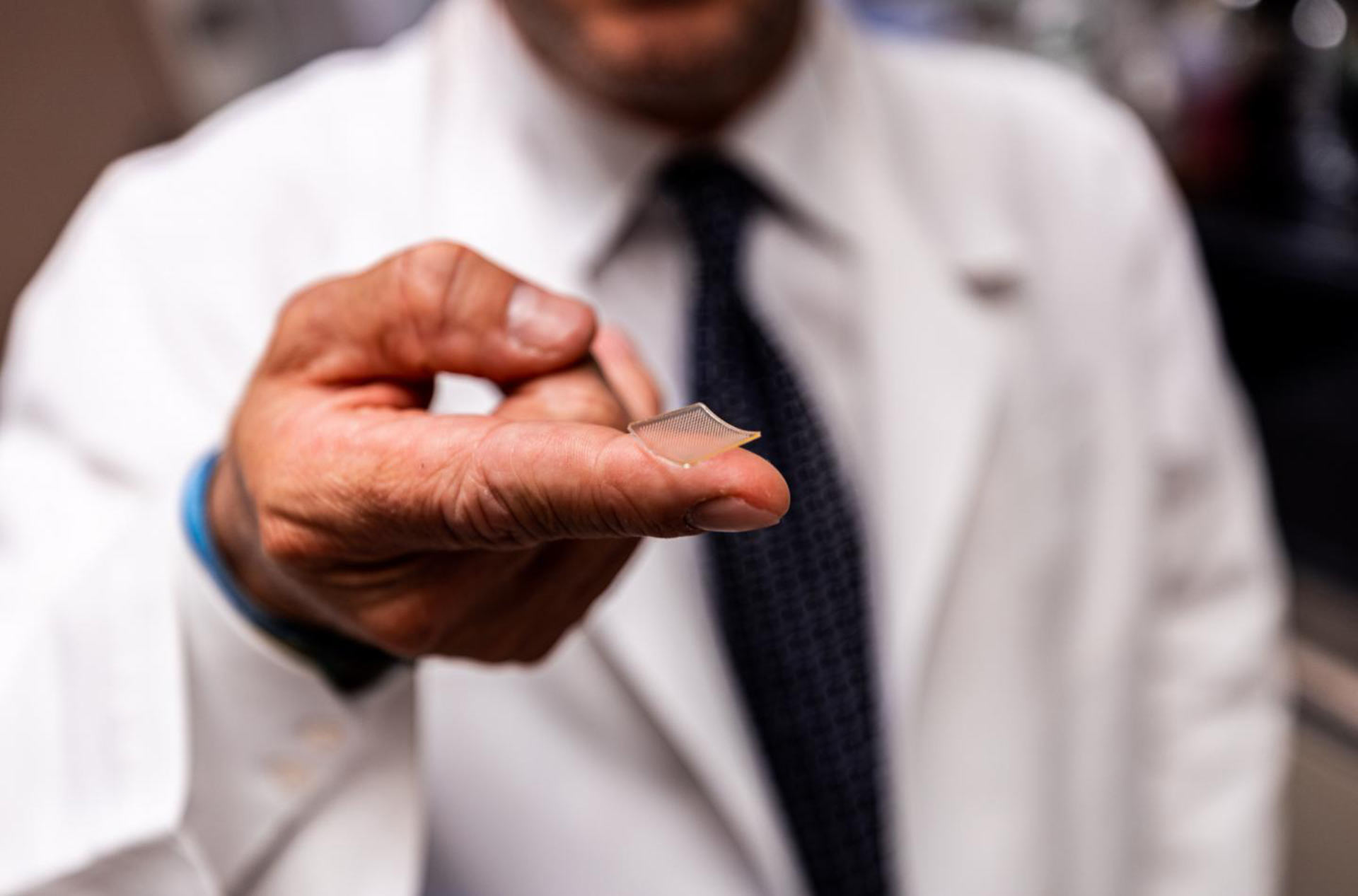

A vaccine patch is a small, adhesive strip – not dissimilar to an everyday plaster – that can be self-administered by patients.

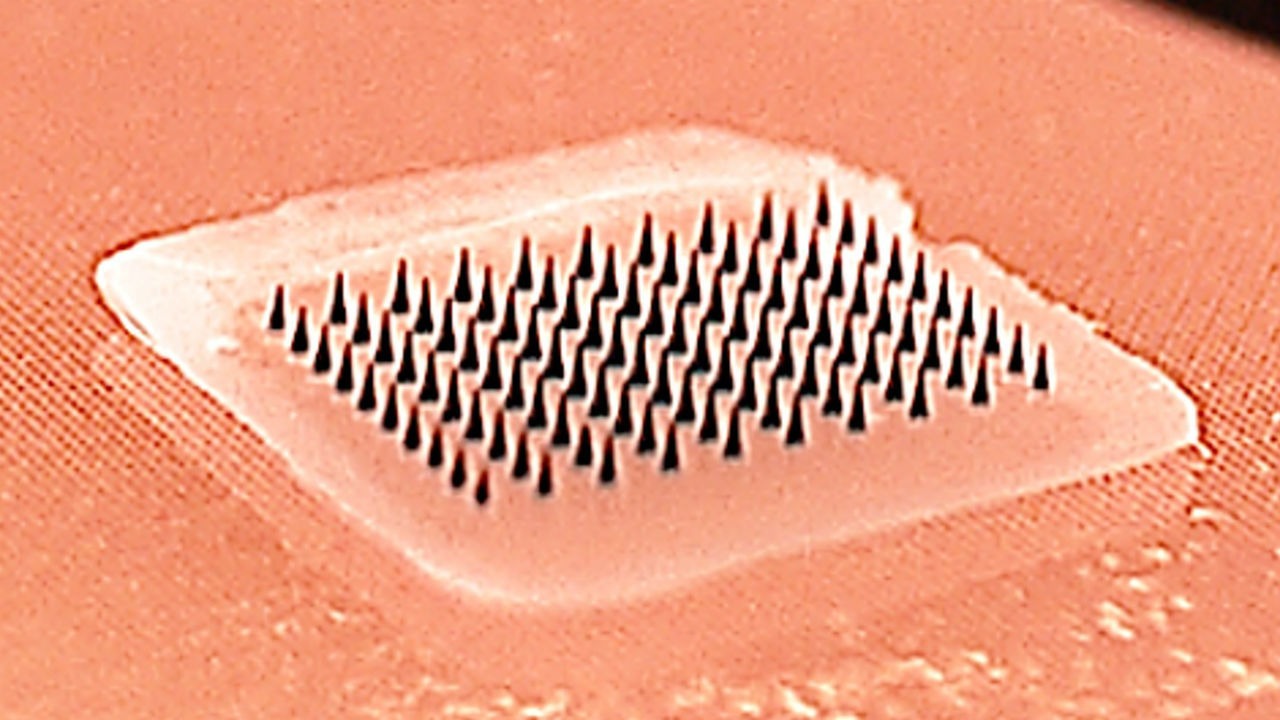

The most common method these patches use to deliver a vaccine dose is via numerous tiny, coated microneedles, which are only a few-hundred microns in length and are therefore just long enough to penetrate the skin.

Because these microneedles are made from water-soluble materials like sugars or polymers, they then dissolve quickly into the skin after use.

The main advantage of this is that it is painless, and could therefore offer people with a fear of needles a minimally-invasive alternative to traditional, injection-based vaccinations.

Another potential benefit held by vaccine patches is the fact that they don’t need to be refrigerated – meaning they could be stored more easily in pharmacies and either purchased by, or posted to, patients – and could remove concerns around disposal or reuse of needles as well.

It has also been suggested that vaccine patches may be more suitable for immunising populations in poorer or developing countries where it’s difficult to store traditional vaccines at a suitable temperature.

Initial trials of the technology

While scientists and researchers had been investigating the possibility of a ‘needle-free’ vaccine for several years beforehand, the first concrete indication that a patch may be the solution came in the summer of 2017.

Emory University – a private research university in Atlanta, Georgia – published the results of a small, phase 1, first-in-human clinical trial in which 100 people were administered with an influenza vaccine via a skin patch.

The results were largely positive, with suggestions that it was just as effective as a standard injection in terms of producing antibodies, and there were also no serious safety-related concerns – with the only adverse effects being faint redness and mild itching where the patch had been applied to the skin.

The researchers involved stated that larger studies would be required to fully ascertain if the vaccine patch was safe and effective, and confirmed they would move on to phase 2 clinical trials involving more people.

However, aside from a team from the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York stating that its own alternative, microneedle-free vaccine patch had shown promise when tested on mice last year, there had been very few reports of further progress into developing an approved product of this kind – until the Covid-19 outbreak.

Who is trying to develop a Covid-19 vaccine patch?

Compared to the relative lack of movement on this front over the past couple of years, there has been an explosion of activity from companies and research teams attempting to produce a patch-based vaccination against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

In April 2020, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine said their vaccine patch containing 400 microneedles – significantly more than the 100 used by Emory University’s – had been tested on mice, and produced Covid-19 antibodies within two weeks.

The team has now applied for an investigational new drug (IND) designation from the US FDA for its ‘PittCoVacc’ patch, and is thought to be moving closer to beginning phase 1 clinical trials involving human participants.

Having received funding from US health department office BARDA (Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority) in late-August, American biotech firm Vaxess Technologies announced on 14 September it was partnering with UK pharma company Medigen to develop a combined Covid-19-plus-influenza patch.

Other teams attempting to develop a successful coronavirus vaccine patch include Italian biopharmaceutical firm Verndari – which also received BARDA funding in August for its dermal VaxiPatch technology – and UK medtech company Innoture, which won a £200,000 ($258,000) grant from the Welsh government for its 3D-printed patch in July.

And, most recently, on 5 October, Australian medical devices firm Vaxxas also secured $22m from BARDA for its own HD-MAP (high-density microarray patch) technology.

While this particular funding is being used to initiate phase 1 clinical studies of its technology involving a flu vaccine, the company has said it is investigating opportunities to use its vaccination platform against Covid-19 as well.

How soon could a vaccine patch be available?

Right now, it is extremely difficult to tell when – or even if – any of these novel microneedle patches could make it through human clinical trials, gain regulatory approval and become available to the public.

It does, however, seem likely that the firms and universities working on them have significantly less manpower and money at their disposal than AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi and the numerous other pharma giants currently racing to develop a Covid-19 vaccine.

Those working on patch technologies are therefore likely to be some way behind these industry heavyweights in their own attempts to tackle the global pandemic.

This notion is arguably confirmed by the fact that several traditional vaccine candidates are now in Phase 3 clinical trials – the final stage of testing in humans – while many of the aforementioned Covid-19 patch devices are only just reaching Phase 1 assessments.

With the WHO (World Health Organisation) stating on 4 September that it doesn’t expect widespread vaccination against the virus to take place until mid-2021, it’s probable that a patch-based alternative will not be available until even later.

Having said that, many have already shown promising signs during pre-clinical testing, and the current climate – in which the entire world is desperate for any innovation that could halt the spread of Covid-19 – means they are likely to be accelerated through the necessary clinical trials and regulatory frameworks as quickly as possible.