The global response to Covid-19 has seen established technologies and novel innovations alike urgently deployed to save lives, and curb the spread of the virus. We take a look at how 3D printing, an emerging technology that perhaps lies somewhere in between the two, has been impacted by the crisis.

As a return to normality draws slowly but surely closer in even the worst affected European countries, it may quickly be forgotten just how dire the Covid-19 crisis was at its peak.

The situation looked especially desperate for Italy throughout much of March and April, with thousands of new infections and hundreds of deaths every day.

Veneto, Lombardy and other northern regions were ravaged by one of the most severe outbreaks of the coronavirus seen anywhere in the world, and shortages of crucial medical equipment — including ventilators — quickly became a pressing concern.

However, one hospital in the city of Brescia had its supply problems eased when local 3D printing boss Cristian Fracassi came forward and offered to help using his company’s technology.

Fracassi, CEO of start-up Isinnova, delivered a 3D printer to the hospital within hours of hearing about its shortages, and was able to print ventilator valves on site for a fraction of the price the original part was reportedly being sold for by a medical device manufacturer.

The speed and minimal cost at which Isinnova was able to provide these venturi valves — albeit under the most exceptional, and urgent, of circumstances — has highlighted many of the known benefits associated with 3D printing as a manufacturing process.

Davide Sher, an additive manufacturing market analyst and technology journalist, believes the global health crisis is shining a light on the potential 3D printers hold.

“Additive manufacturing may be able to play a role in helping to support industrial supply chains that are affected by limitations on traditional production and imports,” he wrote online in the 3D Printing Media Network following the Isinnova case.

“One thing is for sure though: 3D printing can have an immediate beneficial effect when the supply chain is completely broken.

“While there are both copyright issues and medical issues that need to be taken into account when 3D printing any medical product, and a critical one such as a venturi valve, in particular, this case has shown that a life and death situation could warrant using a 3D-printable replica.”

He adds: “As the virus inevitably continues to spread worldwide and breaks supply chains, 3D printers – through people’s ingenuity and design abilities – can definitely lend a helping hand.”

But as traditional manufacturing methods gradually go back online following the pandemic, attention will inevitably turn to how 3D printing can play a more central role in the post-coronavirus world of healthcare.

Pros and cons of 3D printing

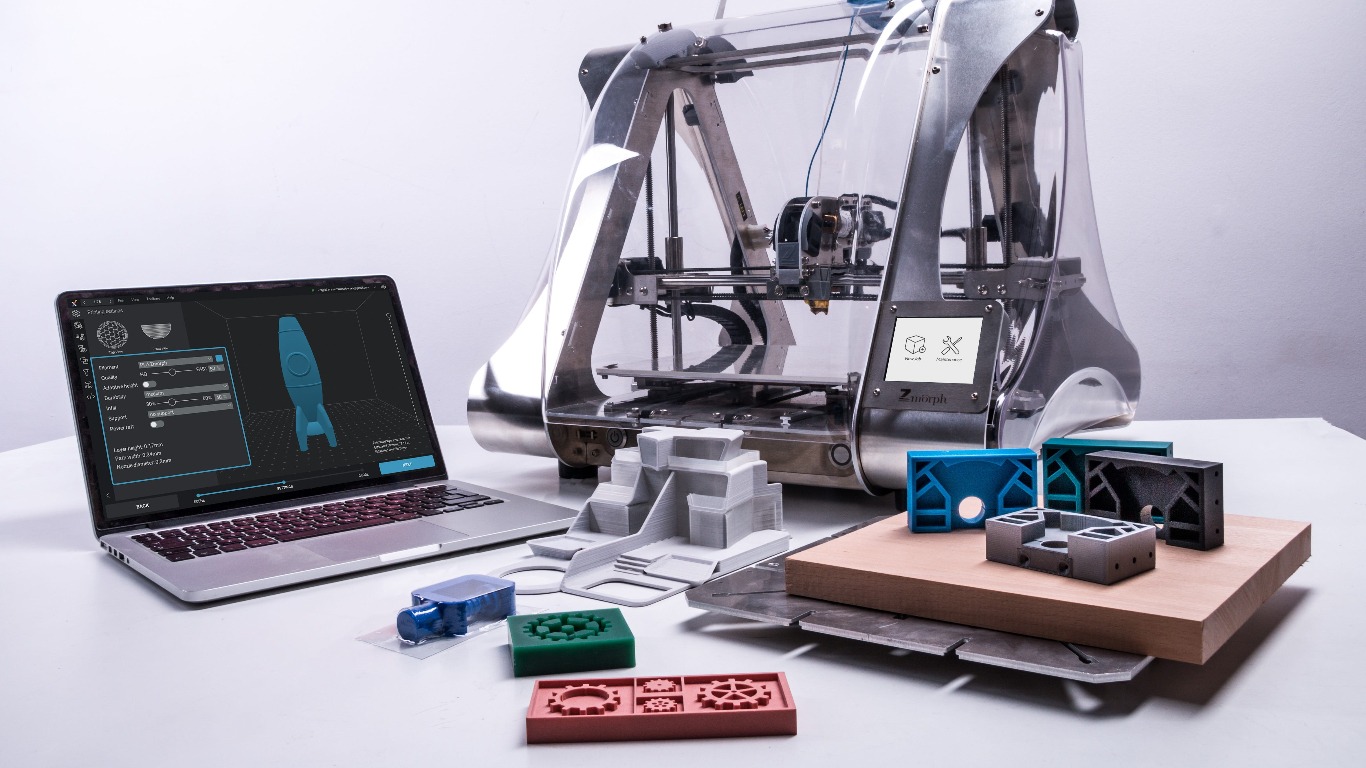

Many of the benefits of 3D printing — also commonly referred to as additive manufacturing because it involves adding layers of material on top of each other to create a single object — apply across a range of industries, including the medical sector.

Prototype devices can be designed and printed rapidly, and this can often be done on site — meaning that, in theory, components can be produced in hospitals to suit their demands for equipment.

All this can be done in a relatively cost-effective way too. 3D printers themselves may be expensive, sometimes costing up to $100,000 per unit — but once this is in place, labour costs are often minimal as a single engineer can start and oversee the whole additive manufacturing process.

However, the true potential of 3D printing in the healthcare sector lies with its design capabilities — which sees it chosen ahead of more traditional, established production means like injection moulding and die casting in certain contexts.

Engineers can re-design and refine objects, endlessly tweaking their geometries and experimenting with a wide variety of materials to build them.

Not only can invasive, patient-specific devices such as implants and prosthetics be customised to suit the recipient’s anatomy, but surgical instruments and other pieces of medical equipment can be altered — and perfected — based on feedback from healthcare professionals.

As well as being able to make unique designs for individual patients, additive manufacturing allows for much greater design freedoms than many other processes, meaning more complex, precise shapes can be created.

But 3D printing — as with any emerging, evolving technology — does have its foibles.

Most notably, the cost of each printer drives up the asking price associated with integrating additive manufacturing for any company, or indeed any hospital, wishing to do so.

Stringent medical regulations, while an important buffer between manufacturers and the commercial market, lead to extensive testing. This makes 3D-printed devices more expensive, and every tweak made to an existing design may require fresh regulatory approval, hampering one of the technology’s greatest merits.

Other drawbacks of additive manufacturing today include the substantial training required to use an industrial 3D printer, legal repercussions for anyone that reproduces a patented design, and the large amount of energy needed to power the printers themselves.

Uses of 3D printing during the Covid-19 crisis

The Isinnova case in mid-March was most likely the first prominent example of 3D printing being used in the fight against Covid-19.

When the supply of ventilator valves at Chiari Hospital, Brescia, ran dry, Fracassi and one of the start-up’s engineers went to the facility themselves and redesigned the necessary component inside six hours.

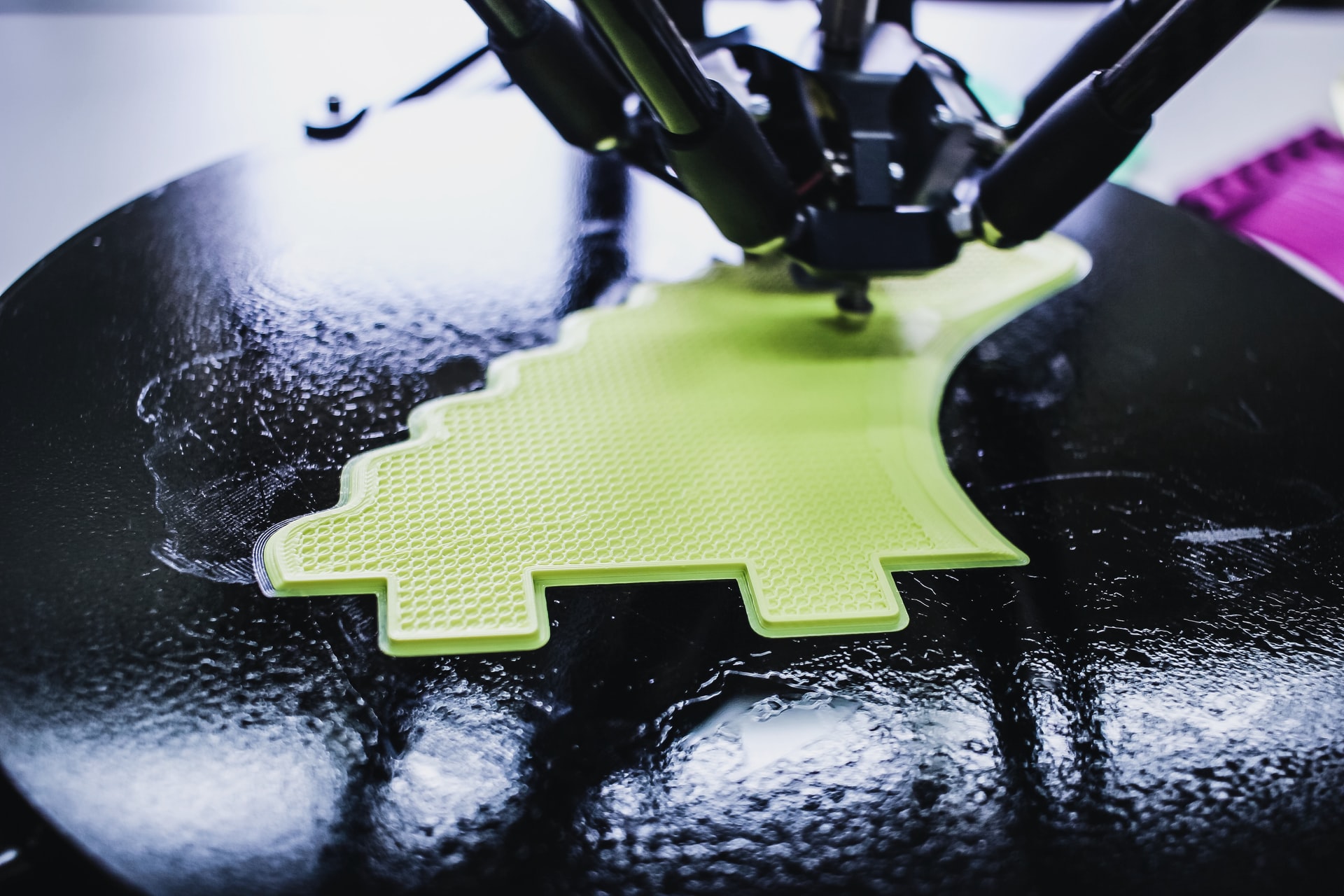

After completing this prototype, and rudimentarily testing the device on patients in the hospital, the company was able to print one valve every hour for just €1 ($1.08) each using a filament extrusion system — a 3D printing process that involves feeding pieces of plastic or metal filament through a heated nozzle layer by layer to create an object.

Reports at the time suggested that 10 critically ill patients had their lives saved after being connected to ventilators using Isinnova’s valves.

Using powder bed fusion (PBF) — a different additive manufacturing process in which a laser melts and fuses a powder to build up layers of an object — another Italian 3D printing firm, Lonati, later printed more of these valves to help meet the Brescian hospital’s needs.

Personal protective equipment (PPE), including face masks and visors, has since been 3D-printed to ease shortages in hospitals across the world too.

In the UK, the 3D Crowd — an 8,000 member-strong group ranging from additive manufacturing CEOs to enthusiasts with a 3D printer in their home — has come together to produce more than 100,000 single-use face shields to plug gaps in the supply chain.

And, in less than a month, BCN3D — a manufacturer of desktop 3D printers based in Barcelona— single-handedly produced more than 4,200 reusable face shields, which have now reached 50 health centres across Spain.

Valdecilla Hospital, located in Santander, Spain, has also used 3D printers sourced from US provider Formlabs to design and print hundreds of swabs — which are used in Covid-19 testing kits to take samples from a patient’s nose or mouth.

Belgium-headquartered additive manufacturing company Materialise has even 3D-printed a customisable, hands-free door handle that allows people to open doors using their arm or elbow, preventing the spread of the virus.

Changing attitudes towards 3D printing?

Traditionally, the healthcare industry has been known to lag behind other sectors somewhat when it comes to embracing newer technologies.

But Richard Hague, a professor of innovative manufacturing at the University of Nottingham in the UK, believes this is not the case when it comes to 3D printing.

“Healthcare is probably one of the best-served sectors that is actually using additive manufacturing today,” he says.

“Things like acetabular cups [an important tool in hip-replacement surgery] and in-the-ear hearing aids are all made using additive manufacturing these days, so it’s actually pretty widely spread.”

For many other patient-specific devices such as dental restorations, custom implants and prosthetics, additive manufacturing is already the go-to production method for many companies as well.

But when it comes to mass-producing one-size-fits-all items — such as surgical instruments, PPE and mechanical components like those used in mechanical ventilators — more traditional manufacturing processes are often preferred.

Despite this status quo, Gaurav Manchanda, director of healthcare at Formlabs, notes that 3D printing has already been used more widely than ever before as part of “bridge manufacturing” — efforts to fill gaps in the supply chain and reduce shortages until traditional manufacturing processes come back online — during the Covid-19 crisis.

“Covid-19 is currently raising the awareness level within the health system for those who weren’t aware of how 3D printing fits in beforehand,” he adds.

“What this all leads to is hospitals taking more ownership of their supply chain — whether that’s for a patient-specific device or a mass-produced device.

“That’s where the beauty of 3D printing lies. It’s versatile, and the same machine can print both, depending on the needs.”

And, as Rodrigo Noble, a digital healthcare expert at analytics firm GlobalData, says, widespread PPE shortages caused by the coronavirus pandemic have become “a proving ground of sorts” for 3D printing.

“The global additive manufacturing community has come together to alleviate shortages, and it will no doubt be interesting to see how big an impact this has had on the industry’s sentiment and views on the technology,” he continues.

“The rapid response and manufacturing capabilities demonstrated by the 3D printing community has been commendable, and vital to the lives of many patients and healthcare workers.

“This push has demonstrated the dynamism of the industry and highlights one of 3D printing’s biggest benefits — print-on-demand.”

Could hospitals use the printing technology to make their own equipment?

Alongside the major manufacturers ramping up production of PPE has been an army of helpers making their own face masks to supply to frontline healthcare workers.

Some of these have been able to call on the use of 3D printers in their home.

While these national efforts witnessed in countries like the UK and US have, to some extent, helped to plug gaps in the traditional supply chain, it is not considered a viable, long-term manufacturing option — particularly in the healthcare sector where regulation and cleanliness are so essential.

“These low-cost, home-based printers that sit on a desk are just not appropriate for manufacturing anything,” says Hague.

“They’re good for making shapes at home but it doesn’t mean you can actually use that shape, or that the materials are going to be sterilisable or robust enough.”

“Industrial 3D printers cost hundreds of thousands of pounds, they’re run by skilled people and are able to make parts for use in automotive, aerospace and other demanding applications.”

Using additive manufacturing in appropriate settings — such as hospitals, and potentially even pharmacies — is considered far more realistic, however.

“I can imagine it being used in the health-based environment where you have small manufacturers with the appropriate equipment, and I can imagine printers in pharmacies printing pharmaceuticals at some stage,” says Hague.

“But it will be in a controlled environment with systems run by a professional.

“Is there any opportunity for hospitals to have systems on site, and to be printing parts out when required? Yes, I think there is.”

In late March — when the number of global Covid-19 cases was still in the hundreds of thousands, rather than millions — Jos Burger, the CEO of Dutch 3D printing firm Ultimaker, told NS Medical Devices the wider use of additive manufacturing after the crisis was “unavoidable”.

Manchanda echoes this sentiment, saying that, once the Covid-19 crisis is over, hospitals all over the world may have an excess capacity of 3D printers they have brought in to ease critical shortages, and are likely to find other uses for them rather than simply returning them to suppliers.

“I would anticipate hospitals taking 3D printers on site – not just to use them as they were before Covid-19, for some dental applications and spare parts, but as more of a factory-in-a-box approach,” he adds.

And, as well as further integrating 3D printing into their everyday manufacturing practices, hospitals may take on more printers — and hire biomedical engineers to operate them — to guard against future crises.

“One trend we’re anticipating is for hospitals to consider production of emergency supplies on site, so they’re essentially de-risking themselves in the event of global supply chain shortages or disruptions,” Manchanda adds.

“Supply chain managers within health systems will be thinking about how to avoid this situation completely in the future.”

How has medical regulation been impacted by coronavirus?

Formlabs — alongside its work in printing testing kit swabs — has produced components for ventilators, respiratory devices and protective face masks, primarily to plug shortages in the US during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Manchanda believes the crisis will ultimately have an impact on the regulatory side of 3D printing — not least because some manufacturers have had more contact with regulatory bodies than ever before over the past few months.

“Before this point, we had been in touch with the FDA from time to time, as needed, but for the past two months we’ve been in touch with it almost daily,” he says.

“So, it’s a different level of collaboration, engagement and communication than ever before, and I imagine the same is true for other 3D printing manufacturers.”

Manchanda says the swab Formlabs has printed for use in hospitals has been shown to be potentially as good — if not better — than the design previously accepted as the “gold standard” in other testing kits.

“I think the crisis will raise questions in terms of the efficacy and the quality of medical devices that have already been on the market for decades without really being reevaluated,” he says.

“Some of these accredited devices are taken as standard until it’s proven otherwise and, often, there’s no reason to challenge the gold standard. Once those standard items are out of stock, it all becomes fair game again.”

Because of the speed at which Formlabs was able to design such an effective swab, Manchanda believes this could lead to a shift in how regulatory agencies such as the FDA approach device-related standards — possibly by attempting to re-evaluate them every five or 10 years to ensure they are as good as they can be.

Under normal circumstances, in a non-Covid world, devices produced using additive manufacturing undergo similar regulatory assessments to medical equipment made in any other way.

Once the specific design has been tested, deemed safe and approved by a regulator, it can be commercialised.

Ultimately, however, any company or hospital wanting to then 3D-print that design would also have to follow the clinical protocols and instructions that come with the design file. This is to ensure that everything previously established about the original design can also be assumed of any subsequently printed parts.

Hague hopes that, despite regulations being relaxed in some cases to ease shortages caused by Covid-19, they remain unchanged following the pandemic.

“I hope products are regulated correctly, and I hope we continue to have safe PPE and equipment that people can use with confidence,” he says.

“The manufacturing method shouldn’t really make any difference in that — we just need safe products.”

Remaining barriers for the printing technology

One of the few silver linings to come from the coronavirus pandemic may be that it opens eyes in the healthcare industry, highlighting the potential additive manufacturing has and the areas in which it could be more widely implemented.

However, it seems unlikely this transition will be without its stumbling blocks.

Several barriers remain, including the unclear — albeit improving — regulatory environment, as well as the cost of buying the printers and insuring any devices made using them.

The fact 3D printing is a relatively new, yet rapidly evolving, technology means limited awareness of — or at least exposure to — additive manufacturing and the workflow requirements associated with it could also be an issue.

Similarly, many places will be 3D printing medical devices for the first time following Covid-19 and will need to employ engineers with the right level of expertise to operate them.

As Hague notes, 3D printers aren’t as simple as “putting pigs in one end and getting sausages out of the other” at the press of a button.

“It will depend on whether a hospital can invest in the skills, and the right people to run the machines, to get the most out of them,” he adds.

Many of these remaining bottlenecks are similar to those already seen in 3D printing’s general uses in healthcare — and, despite the wide array of use cases, have still been present during the Covid-19 crisis.

“What’s happening now is that people are seeing additive manufacturing being used for reasonably useful products,” says Hague.

“As a manufacturing tool it is definitely emerging, but it will not be the be-all and end-all. It will be a tool in the toolbox that should be used appropriately.

“And it’s not really until people start designing their products to be suitable for additive manufacturing, to take advantage of additive manufacturing, that you will get a significant benefit.”

When Isinnova came to the aid of a Brescian hospital in March, the company not only saved lives, but also demonstrated the potential 3D printing has when used in a context that suits its particular strengths.

Now, it will be up to those within the healthcare sector to identify where more of these specific settings lie in a non-Covid world, and deploy additive manufacturing in the areas it is needed most.