Brain stimulation therapy involves sending pulses of electricity to the brain to stimulate neural activity for the treatment of conditions such as depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The therapy typically involves placing electrodes on the outside of the scalp, although it can also require surgery to insert a device beneath the skin in more invasive treatment methods.

Brain stimulation techniques are often used to treat mental health conditions when antidepressant drugs and talking therapies such as CBT (cognitive behavioural therapy) have failed.

Nowadays, such treatments can even be administered at home using simple devices including the Flow headset.

But the history of brain stimulation dates back hundreds of years to a time when medical technology was far more basic.

Early brain stimulation therapy in the 18th and 19th century

As far back as the 1700s, TES (transcranial electrical stimulation) machines for brain stimulation were available to members of the public.

During Victorian and Edwardian times in the UK — the 1800s and early 1900s — these machines used battery, friction or static to generate a low electrical current.

The rudimentary technique could be self-administered, and physicians, therapists and patients alike all claimed it could generate feelings of euphoria and improve mental performance.

However, its use was unregulated, and is thought to have produced side-effects including headaches, dizziness, and nausea.

In 1801, an Italian physicist named Giovanni Aldini used one of the earliest forms of tDCS (transcranial direct-current stimulation) — a non-invasive therapy that is generally considered safer and less painful than other brain stimulation methods.

He administered the treatment to improve the mood of a farmer with a serious type of depression known as “melancholia”.

However, a lack of scientific understanding and appropriate technology to move tDCS forward meant it was soon overtaken by a more concrete discovery in the field.

The introduction of electroconvulsive therapy

By the 1930s, psychiatrists were already using a drug named metrazol to induce seizures and alleviate symptoms of mental illness.

But it was a deeply unpleasant and potentially unsafe experience for patients, and researchers in Italy set about finding a more humane way to trigger seizures.

ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) was first used on a human subject in 1938 by neurologist Ugo Cerletti.

He used a series of electrical shocks to trigger a seizure in a patient with schizophrenia, relieving their hallucinations and confusion, and returning them to a normal state of mind.

Within a few years of its invention, ECT was being widely applied in mental hospitals all over the world.

But through the 20th century it was often used to control difficult patients as much as it was used to improve their mental health. This was famously demonstrated in the 1975 film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Doctors were also not as well equipped to deal with the associated safety risks of ECT — including pain, memory loss, and the physical dangers of having a seizure — as they are today.

Despite growing evidence it could be effective in treating mental health problems, the use of ECT declined in the 1960s and 1970s.

Invasive brain stimulation treatments

The starting point for an invasive method known as DBS (deep brain stimulation) is widely considered to be the work of French brain surgeon Alim Louis Benabid.

In 1987 he discovered that electrical stimulation of the basal ganglia — a group of structures in the brain — could improve symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

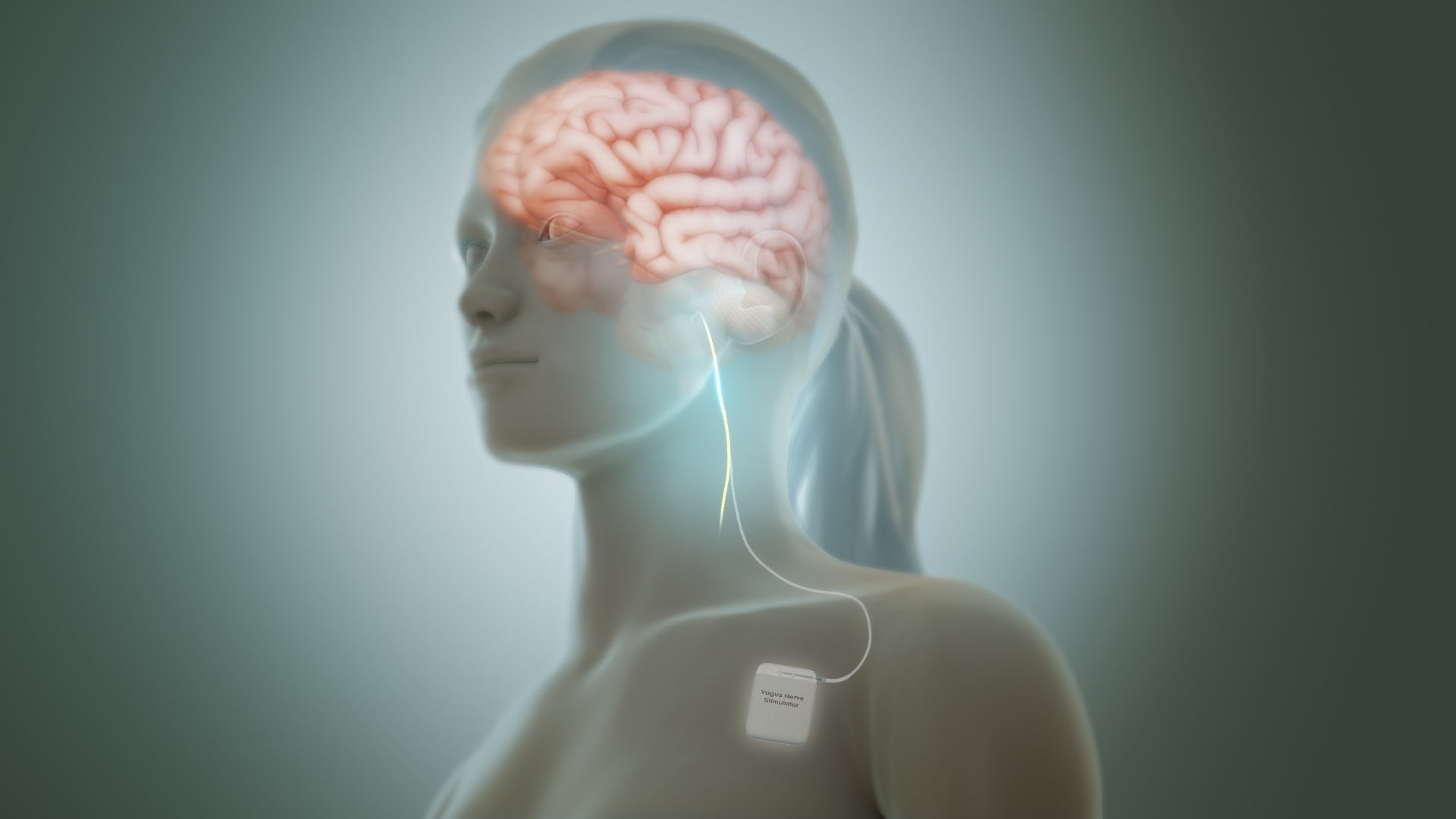

In DBS, a pair of electrodes are inserted into the brain and controlled by a generator implanted in the chest.

It gained US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2002 to treat Parkinson’s disease, and there is evidence to suggests several psychological conditions including OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder), Tourette’s syndrome and depression can be treated using DBS.

However, the fact it is invasive, and therefore carries the same potential side-effects as other forms of neurosurgery including bleeding in the brain, stroke or infection, means it is only considered an option for mental health patients once all other treatments have failed.

Around the same time DBS was first developed, an American neuroscientist called Jacob Zabara found that VNS (vagus nerve stimulation) could reduce or eliminate seizures in dogs.

He reasoned that it could have potential in treating the seizures experienced by humans with the neurological disorder epilepsy.

The first VNS implant device received regulatory approval to treat epilepsy in 1994 in Europe, and gained FDA approval for use in the US in 1997.

VNS involves implanting a device under the skin, which then sends regular electrical pulses through the left vagus nerve — one half of a pair of nerves running from the brain stem through the neck and body.

These nerves carry messages from the brain to the body’s major organs, and to areas of the brain that control mood, sleep and other functions.

VNS received FDA approval for patients with depression in 2005, but it is only recommended for very particular cases of treatment-resistant depression.

The re-emergence of transcranial stimulation

In 1985, the first rTMS (repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation) device was invented by a physicist from Sheffield, England named Anthony Barker to treat depression.

Like the more invasive methods developed in the same decade, rTMS involves sending continuous bursts of electrical current to stimulate neural activity in the parts of the brain associated with mood control.

However, it does not require surgery, but instead uses an electromagnetic coil, which is placed against the patient’s scalp, to deliver a painless electromagnetic pulse.

It is generally considered safer than seizure therapies and more invasive neurostimulation treatments — although it does have some associated side-effects including a short period of headaches and lightheadedness after the procedure.

It took until 2003 in Canada and 2008 in the US for rTMS therapy to be approved for use in treating depression.

Meanwhile, around the turn of the century, tDCS regained interest among neuroscientists as the industry looked for effective treatments with fewer side-effects than antidepressants and other drugs.

This may also have been due to new brain imaging technologies — and possibly the growing popularity of other brain stimulation methods such as rTMS.

Brain stimulation treatments in the 21st century

As well as being used more widely by healthcare professionals to treat depression in doctor’s surgeries and hospitals, tDCS can now be self-administered — just like the earliest forms of brain stimulation in the 1700s.

Swedish medical device company Flow has developed a headset featuring two electrodes that deliver a low-energy electrical current to increase brain activity and reduce symptoms of depression.

The device is intended for use at home, in conjunction with a smartphone app featuring an AI-powered chatbot.

Today, rTMS can be accessed in a number of Smart TMS clinics across the UK, where it is used to treat depression and several mental health conditions including OCD and anxiety. It is also approved for use in treating depression in the US.

Having re-emerged as a mental health treatment in the 1980s, ECT is now the best-studied brain stimulation therapy with the longest history of use, according to the US National Institute of Mental Health.

New technologies, and improved scientific understanding via research studies and trials, have also made its application safer, and it is now considered standard for patients who haven’t responded well to antidepressant drugs.

Psychiatrists estimate that about 100,000 people in the US alone currently receive ECT for conditions including OCD and psychosis.

However, another form of seizure therapy known as magnetic seizure therapy (MST) has also gained some traction in the 21st century, having first been used in 1998.

It triggers a seizure using magnetic pulses, like the ones used in rTMS, rather than electricity, as this is thought to be as effective as ECT without producing as many cognitive side-effects such as memory loss.

While clinical trials of MST have produced positive results in patients with depression and bipolar disorder, there is still limited proof it is safe and effective enough to be used widely to treat mental health problems.

The more invasive techniques — DBS and VNS — are still used today, but only as a last resort when antidepressants, talking therapies, and even other forms of brain stimulation have all failed.

While there is evidence both can be used to treat depression and OCD, DBS is still mainly used on patients with Parkinson’s disease, and VNS is predominantly used to treat epilepsy.

Often, mental health professionals will now also prescribe medication and some form of psychotherapy alongside brain stimulation techniques to maximise the chances of them being effective.